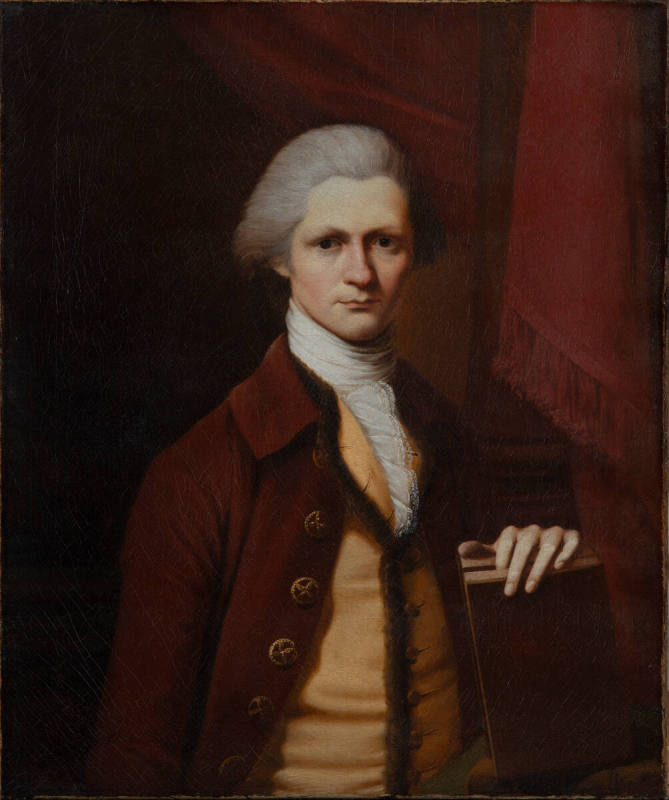

Bushrod Washington

Bushrod Washington commissioned Henry Benbridge to paint this portrait as a gift for his mother Hannah Bushrod Washington. The portrait depicts Washington on the eve of his twenty-first birthday, when he was living in Philadelphia studying law before embarking upon a renowned legal career. In the late spring of 1783, Washington wrote his mother three letters that record how he compared and judged artists, valued their different abilities to paint accurate likenesses, and selected the size of the canvas as much for reasons of cost as for composition. His choice came down Charles Willson Peale and Henry Benbridge, undoubtedly two of the leading portraitists during this era. “There were two Painters, whose talents were great, though in some Respects different,” he confided in Mrs. Washington. “I discovered in Peale’s paintings the most striking likenesses—In Bembridge’s [sic] the most elegant and superior Drapery—Whether I should prefer the first of these qualities or the last in a picture, I was not long in determining, since the principal End, is to give an absent friend, or posterity, an idea of a face whi[ch] they had never seen, or If the likeness then is a Bad one, the most perfect drapery will not stamp its value, any more than a Continental Bill which bears on its face the type of thousand.” When the painting was complete, Washington worried Benbridge may have failed to properly expressed his countenance; yet he was willing to believe his friends, Samuel and Elizabeth Powel, who argued the artist had indeed captured a “mixture of thought with Pensiveness” that suited him nicely. Together the portrait and accompanying correspondence reveal the considerations and decisions sitters faced when having their portraits painted at the end of the eighteenth century and how portraits were ultimately valued, according to Washington, for their ability to remind friends and loved ones in the present, and indeed the future, of one’s face.

Frame:

Appearance: Black painted and parcel-gilt Carlo Maratta-style frame with carved elements. Carved and gilt elements include bellflowers along the sight edge, half-flowers along the outer edge, and a separately carved and applied rope motif set between the cove and outer rim.

Construction: Four lengths of molding mitered and joined by perpendicular splines in the four corners secured with two wrought nails each; two original cast brass, hand-filed hanging loops secured to top edge of the frame with hand-cut screws; modern eye-hooks screwed into the middle of the frame hung with hanging wire.

Published ReferencesCarolyn J. Weekley, Painters and Paintings in the Early American South (Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2013), 382, figure 7.53.

Angela D. Mack, Henry Benbridge: Charleston Portrait Painter (1743-1812), with essays by Maurie D. McInnis, Leslie Reinhardt, Roberta Sokolitz and Carol Aiken (Charleston, SC: Gibbes Museum of Art, 2010).

Stephen E. Patrick, “’I have at Length Determined to Have My Picture Taken’: An Eighteenth-Century Young Man’s Thoughts about His Portrait by Henry Benbridge,” The American Art Journal Vol. 22, No. 4 (Winter, 1990), 68-81, figure 1.

Robert C. Stewart, Henry Benbridge (1743-1812): American Portrait Painter (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1971), 58, figure 64.

There are no works to discover for this record.