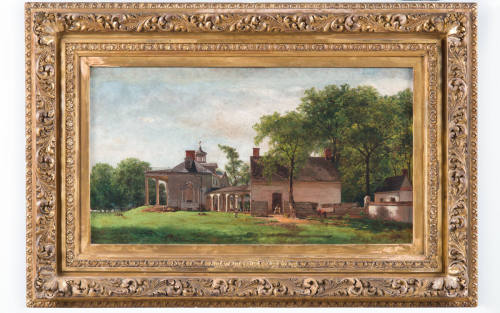

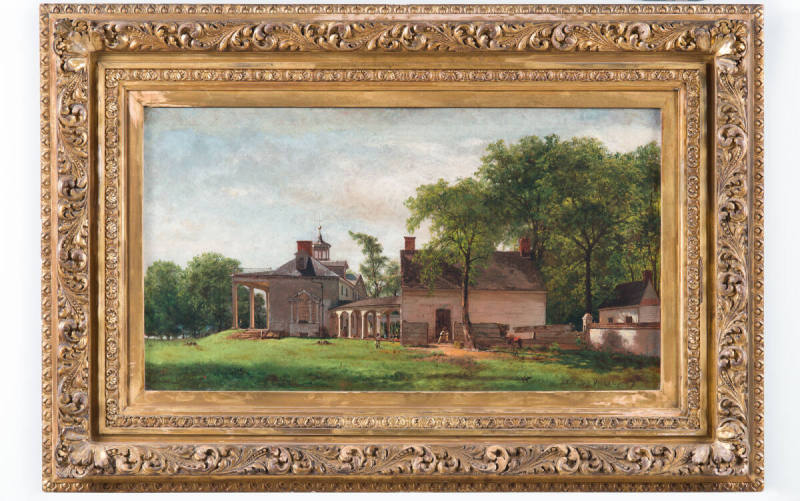

The Old Mount Vernon

In selecting a view of the mansion and its outbuildings from the north (an unusual perspective), Eastman Johnson intentionally created a composition that highlighted the service—and not public—spaces of the plantation, thus revealing the world of the African American laborers, some of whom were enslaved and some free, who kept Washington’s home running. A strong light illuminates the colonnade walkway, which connects the mansion to its north dependency, and draws the viewer’s attention to the men, women, and children outside the gaze of the typical white visitor and in various poses of rest. Far from an idyllic view of Washington’s beloved home, viewers see broken fences, buildings with unpainted walls, and unkempt grounds; in essence, they see a Mount Vernon—and by analogy the economy of slavery—in a steady decline. Between 1857 and 1868, Johnson (1824-1906) produced several paintings depicting the domestic lives of enslaved African Americans with quiet dignity, and his portrayal of The Old Mount Vernon was the first in this series of genre paintings. A genre painter, Johnson visited Mount Vernon in the summer of 1857 with the intention of painting an historical scene of Washington at home, surrounded by his family, guests, and slaves, but he chose instead to capture the plantation as it existed on the eve of the Civil War, increasingly dilapidated and shorn of its former glory. Johnson retained this painting in his personal collection until his death in 1906.

Oil on board genre painting of African-American men, women, and children at rest along the north end of George Washington’s Mount Vernon mansion. The composition of buildings moving from left to right includes the mansion; the covered, colonnade walkway; north dependency (or Servants’ Hall); the gardener’s house; and a broken wooden fence connecting the north dependency and the gardener’s house. A male African-American worker sits in the open doorway to the Servants’ Hall while an African-American child stands nearby in the grass and additional people sit and stand under the colonnade and in front of the east side of the piazza. The buildings are framed by tall trees on the right and an open, atmospheric sky on the upper left. This perspective of the house and dramatic visual focus on the service buildings highlights the relationship of slave spaces to the public spaces reserved for the Washington family, their guests, and visitors to the estate. The painting is framed with a wooden, gilded frame.

Frame:

The frame is in the Barbizon style with gilded wood and composition ornament. The thick outer band of the molding is formed by scrolling acanthus leaves in high relief. The outer band is followed by an inner narrow molding profile and then a molded band of repeating shells bracketed by leaves before a narrow molding profile and a wide plane supporting the painting. The exterior depth of the frame is formed by a deep cavetto extending from the outside edge of the acanthus leaf frieze to a narrow band of molding formed by a repeating shell-like motif. The frame appears to be contemporary with the painting, and therefore, was likely purchased by the artist himself either for display in his studio or his own home.

SignedSigned lower right in brown paint “E. J. Mt. Vernon 1857”. The signature was applied in the same palette as the painting. The signature is partially worn off along the 8 and 5 in ‘1857’.

Published ReferencesEleanor Jones Harvey, The Civil War and American Art (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2012), 185, cat. 63.

Stephen A. McLeod, The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association: 150 Years of Restoring George Washington’s Home, (Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 2010), 148-149, 148.

Christies’ New York, Important American Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 20 May 2009, lot 78.

Laura B. Simo, “’The Old Mount Vernon:’ An Early View Comes Home Just in Time,” in The Annual Report of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union (2009): 30-39, 32-33.

Maurie D. McInnis, “The Most Famous Plantation of All: The Politics of Painting Mount Vernon.” In Landscape of Slavery: The Plantation in American Art, ed. Angela D. Mack and Stephen G. Hoffius (Columbia, S.C.: The University of South Carolina Press in cooperation with the Gibbes Museum of Art/ Carolina Art Association, 2008), 86-114, fig. 69.

John Michael Vlach, The Planter’s Prospect: Privilege & Slavery in Plantation Paintings, (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 19, fig. 1.13.

Teresa A. Carbone, nd Patricia Hills, ed. Eastman Johnson: Painting America (New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art in association with Rizzoli International Publications, 1999), 123, no. 68.

John Davis, “Eastman Johnson’s Negro Life at the South and Urban Slavery in Washington, D.C.,” The Art Bulletin 80, 1 (March 1998): 67-92.

Katherine E. Manthorne with John W. Coffey. The Landscapes of Louis Remy Mignot: A Southern Painter Abroad (Washington and London: Published for the North Carolina Museum of Art by Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), 67, fig. 21.

Patricia Hills, "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes" (Ph. D. diss., New York University, 1977) 48, 203, fig. 28.

Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. “The Right Wing of My Dwelling,” in The Annual Report of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union (1970): 18-22, cover.

John I. H. Baur, Eastman Johnson, 1824-1906: An American Genre Painter (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Brooklyn Museum, 1940), 61, no. 35.

American Art Association, Catalogue of Finished Pictures, Studies and Drawings of the Late Eastman Johnson, 27 February 1907, lot 107.

There are no works to discover for this record.